Level 9

Level 9’s theme is Coastal/Ocean – “Yarlu Yarta” (Kaurna)

- Yarlu (Kaurna) meaning Sea

- Yarta (Kaurna) meaning Country/Land/Soil

Artwork on Level 9

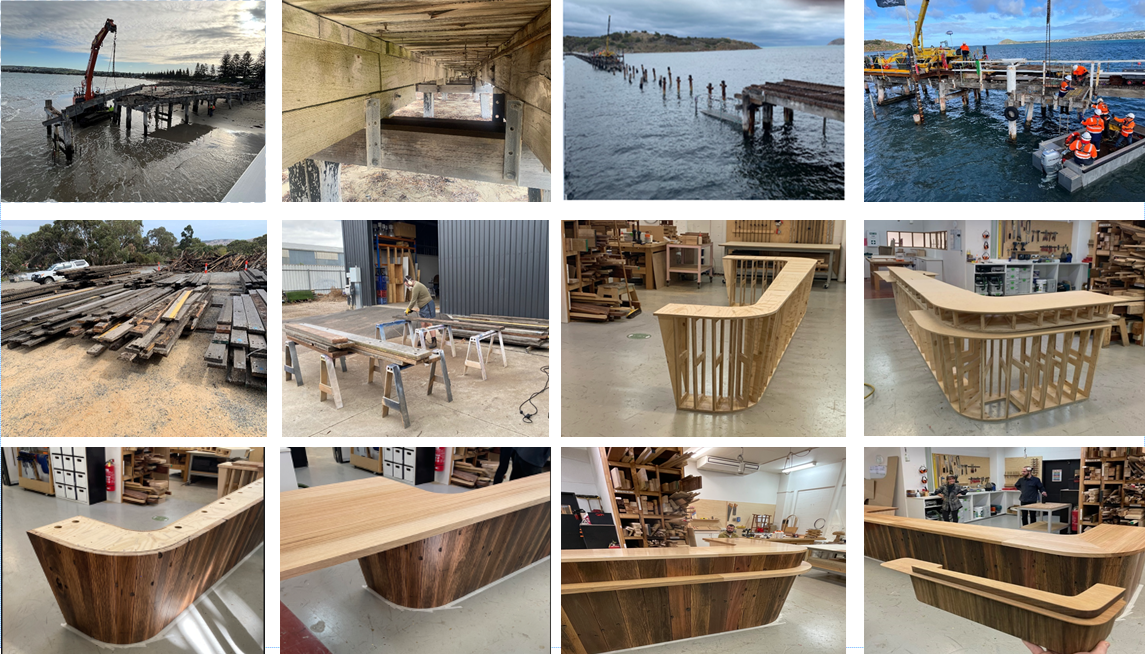

When you arrive out of the lift on level 9, you are greeted by the reception desk. The bespoke reception desk celebrates the Department’s history and vital role of connecting people and places. It was designed by Andrew Carvolth and hand made by the Jam Factory using timbers reclaimed from the old Causeway linking Granite Island to Victor Harbor built in 1867.

In the reception area on level 9 there is a rug that compliments the floor’s theme – "Kauwi Malyu Yarta" (Kaurna).

- Kauwi (Kaurna) meaning water

- Malyu (Kaurna) meaning undulating landscape

- Yarta (Kaurna) meaning Country/Land/Soil

The artwork on the rug depicts the many landscapes within South Australia. In each landscape reflects the Aboriginal language groups and clan groups represented within those landscapes acknowledging first nations peoples and their relationships with the land.

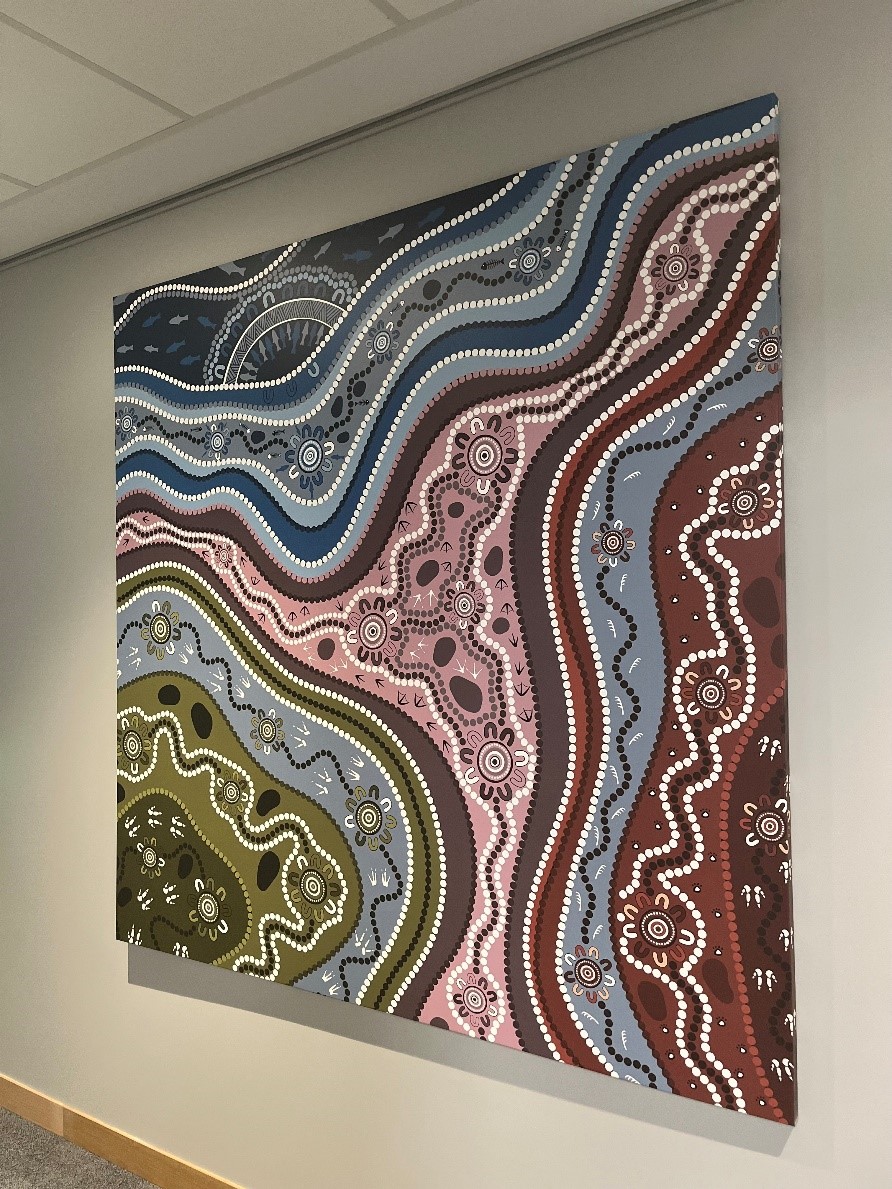

Around the corner from the rug in the most north-eastern hallway you’ll find a painting on display. The artwork depicts the many landscapes within South Australia. In each landscape reflects the Aboriginal language groups and clan groups represented within those landscapes acknowledging first nations peoples and their relationships with the land.

The artwork was produced by Allan Sumner.

As you walk by the meeting rooms check out the artwork on the glass doors and panels. The artwork depicts marine fauna and flora of the South Australian coastal landscape, these animals are hidden within the landscape which also features the iconic White Sea Eagle known as ‘Wirlto Yarlu’ in the language of the Kaurna peoples.

The artwork was produced and designed by Ngarrindjeri man, Allan Sumner.

Once you’ve entered the floor space, from the kitchen area, right around the floor plan even past both stationery rooms and right up to the most southern floor entrance/ exit door, you’ll see on the ceiling the artwork by the Seven Sisters Songlines.

As seen below, the Seven Sisters Songline and Tjukurpa is a significant one for many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Language Groups but it is of particular significance to Anangu. It is a story that celebrates the resilience, trust, and courageousness of women, as well as an instructive and challenging story about how we interact with one another.

These design concepts celebrate the sisters themselves, as well as the significant sites within the landscape that are forged in the wake of the Seven Sisters as they work together to escape Wati Nyura and his shape-shifting trickery.

The design speaks to the landscape and sites created through the sister’s journey.

The artwork was produced by Elizabeth Close in 2021.

Learn more and read the artists' biographies.

Media Room 9.01 - Kurlu

Female Red Kangaroo (Kaurna Language)

Audio recording

Kurlu

* language provided with cultural consent by Kaurna Warra Karrpanthi (KWK)

Seminar / Briefing Room 9.02 - Inparri Kuu

Meeting Room (Kaurna Language)

Audio recording

Inparri Kuu

* language provided with cultural consent by Kaurna Warra Karrpanthi (KWK)

Conference Room 9.03 - Lewis O'Brien

Long-time Kaurna community leader and Elder, who has been integral to Kaurna language revival and has spent many years in student support, teaching and research in tertiary education

Learn more about Dr Lewis O’Brien AO (Kaurna)

Lewis ‘Yerloburka’ O’Brien was born at Point Pearce Mission, Yorke Peninsula in 1930. Uncle Lewis is a Kaurna Elder, but was born on Narungga Country due to his family relocating there, via Poonindie, in the 19th Century following the dispossession of his great, great grandmother Kudnarto’s land holdings near the Clare District. Here he was raised by his gradmother’s brother Lewis Adams, and his wife May, whom he describes lovingly as “super parents” – two extremely knowledgeable and intelligent people with extraordinary practical skills and teaching abilities, who imparted to him “how to learn”, along with other senior community members in his life at that time. Of the old people in the community, and their impact on Lewis as a child, he writes: “They teach you the value of the knowledge and what it’s worth and they do that all your life. I was fascinated by the knowledge they had of teaching, especially the teaching of mathematical concepts.”

At age twelve Lewis and his siblings were separated from family and each other, and he became a ward of the state, living in a series of foster homes, boy’s homes and hostels until age eighteen. It wasn’t until nearly forty years later in 1986 that all of his brothers and sisters would be reunited for the first time, following his younger sister learning of their youngest brother, who had been fostered at six months of age when she was also very young. After she contacted the Department of Community Welfare and ultimately managed to get in touch, the reunion proved to be life changing.

Despite these challenges, Lewis achieved his Intermediate School Certificate in 1946, then gained a fitter and machinist apprenticeship with SA Railways. Lewis attributes his completing the apprenticeship to his love of reading, as his meagre apprentice wages barely covered his board at the hostel, and upon discovering the library in North Adelaide would spend his free time there, devouring several books every night across subjects as diverse as philosophy and psychology, travel, engineering and mathematics. At twenty two Lewis joined the Merchant Navy as a Ship’s Engineer, travelling the world for some years, and continuing to work as a fitter and machinist for thirty years before moving into education.

From the early-1960s Lewis was also involved in much of the early political and community organising in the South Australian Aboriginal community, including the Aboriginal Advancement League, the Aboriginal Community Centre, and the Aboriginal Council of South Australia (formerly the Council of Aboriginal Women of South Australia). Lewis was also the founding Chairperson of the Kura Yerlo (“near the sea”) Council at Largs Bay.

In 1977 Lewis joined the South Australian Education Department as an Aboriginal Education Liaison Officer, supporting Aboriginal students to complete their schooling, promoting Kaurna language and culture, and serving on the Curriculum Committee from 1977–89. He attributed his capacity to engage young people experiencing difficulties to his personal experience of hardship and foster care growing up, and his knowledge of overcoming such obstacles. Lewis also contacted Doreen Kartinyeri about her interest in history and genealogy during this period, assisting her to find a home at the University of South Australia to conduct her research; and helped produce a book for secondary students, published by the Department in 1989, entitled ‘The Kaurna People: Aboriginal People of the Adelaide Plains’, where he sought to “try and dispel the myths that had been talked about Aborigines […]. That sort of nonsense really upset me when I was growing up.” Lewis took the opportunity of the publication to write about his own family history as well, detailing the dispossession of his family from ‘Block 346’ and the story of Kudnarto he had begun researching when he was seventeen.

Uncle Lewis has been a key figure in the process of reviving the Kaurna language, and initiating its use and teaching, in close collaboration with Dr Alice Rigney and Josie Agius. He and Alice established ‘Kaurna Warra Pintyarnthi’ with linguist Dr Rob Amery at the University of Adelaide in 2002, building on their language reclamation efforts since at least the 1990s, and collaborating with many other Elders and language enthusiasts, particularly from related languages including Narungga, Nukunu and Ngadjuri. This work has produced a number of publications, children’s books in Kaurna, language teaching programs and other resources, and the gradual development of a sufficient lexicon and grammar for Kaurna to become a teachable and functional auxiliary language, providing important pathways to community development, cultural identity and empowerment.

Uncle Lewis’ contributions to education also include teaching, research and student support in the tertiary sector, where he was a founding member of Wilto Yerlo [now Wirltu Yarlu] in 1996 – supporting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students at the University of Adelaide; as an Adjunct Research Fellow undertaking teaching and research at the David Unaipon College if Indigenous Education and Research (DUCIER), University of South Australia; and at Flinders University, as an Elder on the Indigenous Health Professional Education Advisory Committee, Patron/Elder-in-Residence to the Indigenous Preparation for Medicine Program, and curriculum development and teaching within Yunggorendi First Nations Centre for Higher Education and Research. In his citation for the Award of the Degree of Doctor of the University at Flinders University in 2012, it was remarked that:

“Overall, Uncle Lewis O’Brien’s activities have been central to a re-inscribing of a Kaurna presence into the Adelaide topographical and cultural landscape and an imbrication of vital Aboriginal knowledge, protocols and conceptualisations into the national purview. His unique body of work, and his specific contributions to Flinders University, both substantiate this recommendation for awarding the Degree of Doctor of the University (DUniv).”

Over the years Uncle Lewis has also consulted on a number of public place naming and art projects, including for Adelaide City Council advising on Kaurna place-names and walking trails, and public art projects such as ‘Kaurna Pillars’ at Adelaide Railway Station, 2002, and ‘Two Kaurna Shields’ in the city’s East in 2000.

Uncle Lewis was also the Chief Investigator on the Australian Research Council (ARC) project: ‘Indigenous Knowledge: Water Sustainability and Wild Fire Mitigation’, working towards “positioning an Indigenous philosophical standpoint that will bring a greater focus to Indigenous understandings of our natural world and the relationship between humans and the natural world, particularly in an era of climate change.”

Uncle Lewis has been honoured by many distinguished awards, including:

- NAIDOC Elder of the Year, 1997;

- Citizen of Humanity Awarded by the National Committee of Human Rights, 2009;

- Centenary Medal, 2001;

- An Honorary Doctorate from Flinders University, 2011; and

- Officer of the Order of Australia, 2014, “cited for his distinguished service to the Indigenous community of South Australia as an elder and educator, and for promoting and protecting Indigenous heritage and culture.”

Conference Room 9.04 - Josie Agius

Pioneer of Aboriginal Health Work, education, and Indigenous Youth Performing Arts, and well known for her Welcomes to Country

Learn more about Aunty Josie Agius (Kaurna / Narungga / Ngarrindjeri / Ngadjuri)

Josie Agius (née Warrior) was born at Wallaroo, South Australia in 1934 to Katie Edwards and Fred Warrior, one of five siblings including her brothers Vince (Copley) and Colin, and sisters Winnie (Branson) and Maureen. The family lived at Wallaroo for Josie’s first few years, recalling “mum donkeying me from Wallaroo to Kadina,” where she worked doing housework, while Josie stayed at the playground. Their father Fred died when she was about four. When Josie was seven the family moved to Point Pearce to live with her grandparents Joe and May Edwards, where she stayed while her mother moved to Adelaide for work, taking Winnie with her, and sending clothes and money back to the mission. After attending school and living at Point Pearce for about four years, Josie moved to Adelaide and lived in Mile End with mum, now attending Thebarton School with her siblings, until Katie remarried to Allan Copley, and they once again relocated, this time to Leigh Creek. By the time she left school at fourteen, Josie was living and working in Alice Springs, washing medicine jars, working at a café, and doing housework.

Josie then moved back to Yorke Peninsula at Pine Point, where she lived with Winnie and their mum, Katie, until after she died when Josie was 18. Here she worked on a farm for a time, which she remembered fondly, working with good people and learning how to milk the cows, but before long was on the road again, this time back to Adelaide where she got a live-in job at the Methodist Ladies’ College (later renamed Annesley College), before waitressing at the Franklin Hotel.

After getting married to Fred Agius, the couple moved to Mount Gambier and had two boys, Freddie and Raymond, then moved to nearby Port MacDonnell. After once again returning to Adelaide, the family stayed with various relatives before settling into their own place at Taparoo, where their daughter Kate was born, and where Josie stayed for near to the rest of her life, over more than fifty years.

Following a phone call from her brother Vince, who was working in Canberra at the time with Charlie Perkins, Josie started her first job back in Adelaide in South Australia’s first Aboriginal Health Unit based in Norwood, where she stayed for about seven years alongside Sandy Miller, Auntie Perlie Dookie, Margaret Hampton, Margaret Giles and others. Now she had to learn how to drive, with her husband along the Port River, and loved working in the community and re-establishing connections with extended family. As well as the community work such as visiting Aboriginal families with the nursing sisters; supporting new mums at home; visiting Point Pearce and Raukkan with Auntie Pearl; and accompanying women from remote communities to second hand shops and appointments; the team attended conferences interstate and established a cultural framework for how hospitals and community health services worked with Aboriginal people.

After taking some time off work around the time that her husband died and she became a grandmother, Josie started working at the Taperoo Primary School as an Aboriginal Education Worker. She was also working with Kaurna Warra Pintyanthi on Kaurna language projects with Rob Amery, as well as Narungga language revival, and after seven years at Taperoo, started working across schools doing cultural and language education, and telling stories about her life and what she had gone through: “with the Assimilation Act, and […] you know how the police used to come and take you away and all that” – recalling how many of the kids had no knowledge of this recent history, and often couldn’t believe that these things happened. In this way, reminiscent of her commitment to community engagement in health, Auntie Josie got to know all the kids in the Port Adelaide area, and took pride in remaining ‘Auntie’ to many, both Aboriginal and otherwise, who would come up and introduce her to their own kids in later years.

After undertaking study for three years at Tauondi College in Tourism and Language, Auntie Josie started working at the Port Youth Theatre Workshop, building up Aboriginal community involvement and ultimately evolving into Kurruru Indigenous Youth Performing Arts, providing an extensive performing arts program with a focus on cultural maintenance and leadership, and contributing to a range of festivals and community events. Auntie Josie was also a passionate supporter of local sports, particularly involved in netball and football, where she is recognised today as Patron of the Aboriginal Power Cup and eponym to the Josie Agius Netball Cup in the annual South Australian Aboriginal Cultural and Sport Festival.

It wasn’t until later in life that Josie and her brother Vince became concretely aware of their Ngadjuri and Kaurna heritage, explaining in conversation with Sue Anderson in 2000 that, while they always knew that their Grandfather Barney (Fred Warrior’s father) came from the north, they were too young at the time they knew him on Point Pearce to understand more, and wouldn’t learn much more about their shared Ngadjuri ancestry until research undertaken for projects including the book collaboration ‘Ngadjuri: Aboriginal People of the Mid-North of South Australia,’ and discussions for a proposed Ngadjuri Interpretive Centre in Riverton. To this end, she became very interested in later years in learning more about this heritage, considering it a “catch-up period,” and trying to find out what’s happening, look at the country, see the sites, and do more research. She also perceived projects like the Riverton Interpretive Centre, and the greater visibility of Ngadjuri presence and history on Country as being an important step in Reconciliation; and celebrated the cultural pride she saw in the young ones coming through.

Before she died in late 2015, Auntie Josie had become well known for her Welcomes to Country in Kaurna language, representing the Kaurna people as a Senior Elder at a great many important events, and noted for her wit and sense of humour. She has been honoured in many ways over the years: inducted into the SA Women’s Honour Roll in 2009; an eponymous annual award for Youth Achievement in her local City of Port Adelaide Enfield’s ATSI Awards Program; as Patron of the NAIDOC SA Awards; and winning the Premier’s NAIDOC Award in 2014. Auntie Josie was appointed NAIDOC Aboriginal of the Year in 1990, the South Australian Ambassador for Adult Learning in 1998, and the Centenary Medal for service to the community in 2001.

Conference Room 9.05 - Alice Rigney

Founder and inaugural principal of the Kaurna Plains School, and first female Aboriginal school principal in Australia, and leader in Kaurna language revival

Learn more about Dr Alice Rigney (Narungga / Kaurna)

Dr Alice ‘Alitya’ Rigney was an Elder of the Narungga and Kaurna Nations and a strong leader in Aboriginal education in South Australia. Alice was born at Point Pearce on the Yorke Peninsula and maintained a strong connection to that community. She describes the mission at that time as being an “apartheid situation” where educational opportunities were limited for most, with the local school finishing at year 7. The children from Point Pearce Mission were not permitted to attend the local non-Indigenous schools. Growing up in this small and tight-knit community cultivated deep values of responsibility, respect for Elders, and the importance of giving back to the community. These values would later become the hallmark of Alice’s life, career and leadership.

Drawing on the traditional teachings from her Elders and the benefits from a western education, Alice succeeded at school. These positive experiences were the foundation to her philosophy that schools must create nurturing environments not only for a career, but in developing learners’ pride and competence in their Aboriginal culture and language.

Alice was part of a small group of girls who were given an opportunity to pursue a Nursing career in Adelaide. Originally wanting to pursue Medicine, she was counselled against this due to the prejudice and barriers to women and Aboriginal people of the era. This experience of encountering unjust barriers instilled a strong sense of the importance of “stamina and strength and support” which she later brought to her role as leader, teacher and mentor in educating new generations of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Children. Alice cited role models including Ivaritji (Amelia Savage), Ivy Karpany, Gladys Elphick, Lowitja O’Donoghue and Ngingali Cullen (formerly Audrey Kinnear) from her days in nursing.

Ultimately, dissatisfaction with her thwarted ambitions in medicine led her to return to Point Pearce where she married Lester Rigney and later became interested in education. She was teacher’s aide at the Point Pearce Mission Kindergarten where she became co-director with Elizabeth Newchurch. After several years in roles in Maitland and back at Point Pearce at the Kindy and with the Council, Alice became determined to once more relocate to Adelaide, this time with family in tow “on a whim and a prayer”, to get her full formal teaching qualifications, and was soon the only Aboriginal person in a large cohort at the De Lissa Institute, South Australian College of Advanced Education, and then on to her first teaching placement in 1980.

In 1985 Alice was recruited to the Education Department’s administrative ranks, becoming a strong advocate for Aboriginal schooling and to recruit more Aboriginal teachers and community education workers. She would later work closely with Aboriginal parents to establish the first urban Aboriginal school in Australia – the Kaurna Plains Aboriginal School at Elizabeth. As its inaugural school Principal, Alice led the Kaurna Plains School for thirteen years until retiring from teaching. In her retirement speech, she claimed “when the Principal position was advertised, I decided to apply, because back then there were no Aboriginal Principals around and our kids needed role models.”

Alice was the First Aboriginal Female School Principal in Australia. She described this period as a “magical time” in her life, with strong Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal leaders who fought collaboratively for inclusive education environments that recognise their cultural backgrounds and provide students with a positive foundation in all academic areas. In 1991 Alice won the Australia Day Honours Public Service medal, and in 1998 received an honorary doctorate from the University of South Australia in recognition of her work in Aboriginal Education.

After retiring from teaching, Dr Rigney continued her work for the community in various capacities, including with the South Australian Guardianship Board and Aboriginal Education, Training and Advisory Committee, and as the 2000 Ambassador for ‘Dare To Lead’ and the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations.

She was also instrumental in the process of reclaiming the Kaurna language, working with Dr Lewis O’Brien, Dr Rob Amery and others to establish ‘Kaurna Warra Pintyarnthi’ at the University of Adelaide in 2002. Interviewed for ‘Kaurna Warra Ngayirda Wingkurilla (On the Airwaves)’ in 2013, Auntie Alice reflected on this journey as such:

“It’s a Kaurna language revival movement, and I’ve been involved since day one. And let me tell you: it’s been just a magic journey and I just absolutely love it because reclaiming language is re-empowering Kaurna people.”

Alitya passed away in May 2017, aged 74, and was posthumously made an Officer of the Order of Australia in the 2018 Queen’s Birthday Honours.

Meeting Room 9.06 - Winnie Branson

A great community organiser who always worked hard to benefit her people, and State Secretary of the Federal Council of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders

Learn more about Winnie Branson (Narungga / Kaurna / Ngarrindjeri / Ngadjuri)

Winnifred Lillian Warrior was born in 1927 to Kathleen (née Edwards) and Fred Warrior, the eldest of five siblings to grow up in a family that encouraged a strong commitment to working for Aboriginal equality. Winnie grew up on Point Pearce Mission, where her life and the lives of other community members were dictated by restrictive Government policies and surveillance. Like most young Aboriginal women in that era, Winnie was sent to work as a domestic servant at the decree of the Aborigines Protection Board from about age 14.

After Winne’s father Fred passed away, her mother remarried and moved to Leigh Creek, and later to Alice Springs where Winnie met her future husband David Branson. With their six children – Fred, Patricia, Roslyn, Betty, David and Vincent – they moved back to the Yorke Peninsula at Pine Point for a time, and ultimately settled in Adelaide. This is when Winnie became involved in the growing Aboriginal activism of the era advocating for better support and living conditions for Aboriginal people who had left their regional homes to live in Adelaide.

Winnie was among the founding members of the new Aboriginal Progress Association (APA) and in founding the Nunga Football Club of Adelaide – commemorated today in the perpetual ‘Winnie Branson Cup’ presented to the winning football team at the annual SA Aboriginal Football and Netball Carnival. Winnie saw football as a powerful way to keep Aboriginal families in the community together, to share family news and discuss political ideas.

In 1967 Winnie was elected State Secretary of the Federal Council of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders (FCAATSI). From the early 1960s Winnie had been attending the national FCAATSI conference in Canberra as a member of the Adelaide Delegation, identifying the shared issues facing Aboriginal peoples across Australia whilst advocating an emerging national agenda on Citizenship reform and land rights. FCAATSI was instrumental in campaigning for the historic 1967 Referendum to remove discriminatory clause in the Australian Constitution and create conditions for a national approach to Aboriginal Affairs. Winnie was part of the delegation of representatives in Canberra a month before the referendum to lobby MPs in publicly supporting the ‘YES’ vote and making the case for Constitutional reform. In May 1967 an historic majority of over 90% of voters favoured the changes, the largest in Australia’s history of Constitutional reform.

Winnie was also involved in establishing the Council of Aboriginal Women of South Australia (CAWSA), the Aboriginal Legal Rights (ALRM) and the Aboriginal Community Centre (Nunkuwarrin Yunti). Winnie was a great community organiser around whom people would naturally gather, and was renowned in the community for her capacity to work productively with Government and other institutions for the benefit of Aboriginal people. Winnie passed away in 1972, with a proud legacy of improving the lives of Aboriginal people in Australia.

Innovation Hub 9.07 - Wangka Kuu

Talking Room (Kaurna Language)

Audio recording

Wangkawangkanya Kuu

* language provided with cultural consent by Kaurna Warra Karrpanthi (KWK)

Meeting Room 9.08 - Ivaritji

Learn more about Ivaritji

A gentle misty rain Ivaritji is a Kaurna ancestor, who was said to be born at Port Adelaide in the later half of the 1840’s. Ivaritji was the daughter of Ityamuiipinna ‘King Rodney’ and Tangkaira ‘Queen Charlotte’. When Ivaritji died in 1929, she was said to be at the time the last of Kaurna ancestry and the last fluent speaker of the Kaurna language. |

Multi-purpose Room 9.09 - Karra

Red Gum (Kaurna Language)

Audio recording

Karra

* language provided with cultural consent by Kaurna Warra Karrpanthi (KWK)

Meeting Room 9.10 - Tarnta

Male Red Kangaroo (Kaurna Language)

Audio recording

Tarnta

* language provided with cultural consent by Kaurna Warra Karrpanthi (KWK)

Meeting Room 9.11 - Kadlitpinna

Learn more about Kadlitpinna

Kadlipinna

Kadlitpinna was selected in memory of his role as honorary constable and renown as a ‘military genius’.

Meeting Room 9.12 - Tangkaira

Learn more about Tangkaira

Tangkaiira (Ityamaiitpinna’s wife, refer Ivaritji) – selected because of family connection |

Meeting Room 9.13 - Wauwe

Learn more about Wauwe

Wauwe (Kadlitpinna’s wife) – selected because of family connection (refer Kadlitpinna)